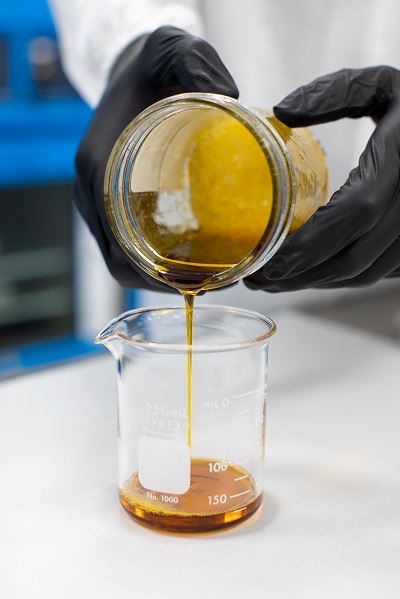

After building a cannabis brand with a cult following, Union Cannabis Group is licensing out its expertise. All photos courtesy of Dabstract. © UCG Inc. 2020

After decades of producing flower, Sushanta Parikh built a cult following among cannabis connoisseurs in California and Washington with the award-winning Dabstract brand, which has branched out from the popular forms of concentrates — such as oil for vaporizers and shatter — and helped popularize new trends like crystalline and live resin.

As CEO of Union Cannabis Group, Parikh knew the company would have to remain small to ensure the integrity of its artisan brand, but it would also need to expand into new territories in order to keep growing profits.

So Parikh, along with chief operations officer Derek Thiel, chief technology officer Dylan Thiel and chief legal officer Eli Korer, designed a business model that allows UCG to do both. Unlike most cannabis companies that rely on securing licenses and building their own facilities to expand into other markets, UCG’s main channels of business are licensing its intellectual property — either the Dabstract brand or its manufacturing processes — and, in the right situations, as operational partners.

“That’s part of the business model,” Parikh says. “We’re not necessarily the license holders in the state.”

Proof of Concept

The Dabstract brand has garnered a loyal consumer base in Washington’s oil market with award-winning products and massive market penetration due, in part, to a partnership with its biggest client, Grow Op Farms, Washington’s top cannabis producer.

During the first few years of adult-use cannabis sales in Washington, UCG white-labeled cannabis products for Grow Op Farms, but by 2015, with that company growing exponentially, CEO Robert McKinley wanted to build an on-site extraction facility at the Grow Op headquarters in Spokane.

McKinley and Parikh struck a deal in which UCG would design the lab, get it permitted, install the equipment and train Grow Op staff on extraction operations in exchange for ongoing royalties from licensing.

Parikh says the deal with Grow Op provided UCG with a huge footprint in Washington and allowed the company to transition to new markets. Today, licensing is UCG’s primary source of revenue, as the company collects royalties from the use of its Dabstract brand and the manufacturing IP used to make a variety of concentrates. The IP includes trade secrets, proprietary processes and trademarks, as well as “a number of engineering and process patents that are pending,” Parikh says.

From August 2019 to August 2020, sales from UCG licensed products, including Dabstract in Washington, totaled $16.4 million.

To keep the company lean, Parikh says UCG sends only one or two employees to stay on at the contracted facility while the rest of the crew is actually employed by the licensor. Currently, UCG has 13 employees, but manages more than 80 workers through its licensing program.

UCG supplies its partners with 100 SOPs covering everything from administration to post processing.

A Compelling Offer

Although the cannabis plant is simple enough to grow in a closet, the legal industry is extremely convoluted, with a plethora of location-specific and ever-changing rules, regulations and prerequisites that stifles progress for many operators who simply want to grow and sell the plant.

When it comes to extraction and processing, regulators add several additional layers of complexities.

Plus, Parikh says, it’s still a nascent industry in terms of access to talent, scientific knowledge, manufacturing processes and middle management, among other areas. From the perspective of developing a multi-state company, it’s vastly different than almost every other industry in North America.

“You could be a Subway licensee in any state, and you’d know exactly what you’re getting,” Parikh says. “That kind of pathway doesn’t exist yet in cannabis. You really have to look at the regulations. You have to understand what your product outcome goals are so that you design the facility in the right way, you get it permitted in the right way, and you get the right equipment.”

Parikh says those are the areas UCG thrives. He says a lot of the companies he talks with are startled to find out how fragmented the extraction market is. The regulations vary substantially from one municipality to the next, making it difficult to build a business model that works in multiple jurisdictions.

“Cannabis processing is not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ industry and each site or process will need its own tailored program,” Derek Thiel says.

Depending on the variables involved, Thiel estimates that it takes UCG three to nine months to set up a new processing facility. After that, he says, there is a three- to six-month launch window where UCG trains staff, oversees the first waves of production and implements its standard operating procedures.

Thiel says the initial setup of a processing facility is rife with potential pitfalls. Companies need to be aware of the mechanical limitations of a specific building’s infrastructure, hire capable operators, manage the installation budget and know what regulators will allow them to produce. These factors can “make or break a startup production facility,” he says. “Far too often, we see groups overlook a critical piece early in the project that results in long delays or even projects running out of funding and going under.”

The most common culprits of project delays are related to site selection and a poor understanding of state and local regulatory requirements.

In addition to the Dabstract brand, UCG licenses its intellectual property for manufacturing concentrates.

Once a facility is functional, Thiel says SOPs are essential to refining operations. UCG has 100 SOPs within five categories that cover administration, packaging, extraction, post processing and the intake, storage and preparation of biomass.

“Oftentimes we encounter facilities that do not have their SOPs built out and updated, and the employees and operators are conducting their jobs by memory and repetition,” Thiel says. “When things go wrong, it’s much more difficult in these situations to determine where the fail points are or how to improve and make your results better.”

The Right Partner

UCG’s model has been fruitful enough that the company is set to expand into California, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nevada, Ohio and Canada in 2021. Parikh says part of what makes the model work so well is the caliber of its partner operations.

“You really need to search out the right operators,” he says. “It goes back to real business fundamentals that every other industry employs. You want to vet prospective investors or facility owners. You want to look at all the operating agreements, the corporate organization documents, the investment documents. You really have to do a pressure test.”

When vetting potential partners, Korer says it is essential that negotiations start with the less-fun aspects of building a relationship such as the key roles and responsibilities of both parties, how daily decisions are made, who is responsible for funding and what happens if there is a deficit of funds. Korer says these concerns, along with dozens of others, need to be ironed out before the companies start dreaming up cool branding ideas.

“It is a red flag if these problems cannot be solved at the onset of a potential business relationship, because they will become problematic and costly issues down the line,” he says, adding that negotiated terms need to be written out in contractual agreements. “Good paper keeps good friends.”

Parikh says UCG has looked closely at opportunities in Oregon and Colorado, but it’s the newer markets that have the most potential to license the Dabstract brand and help partner companies produce high-quality concentrates with lower margins for error.

“Ultimately the future is on the East Coast,” Parikh says.