An experiment on the shelf stability of cannabis flowers

By Nick Mosely

Like any agricultural commodity, marijuana has a shelf life.

There must be some period of time after which the product has lost its optimum flavor or effect or is no longer fit for human consumption. In other words, at some point the cannabis is no longer representative of the quality advertised by the producer.

Unlike other agricultural commodities, standards do not exist in the cannabis market that specify how long a product should remain on the shelf or if/when it should expire.

About the Research Methods

Following a proposed change to quality assurance standards in Washington, Confidence Analytics conducted a research experiment to learn more about the shelf life of cannabis.

The pool of samples examined in this experiment was selected out of convenience; Confidence Analytics, a state-certified cannabis testing laboratory, stores samples for several months before destroying them, which allowed its scientists to retest some samples to evaluate trends over time as the material decays. The company investigated changes in viable microbial bioburden and cannabinoid content over a period of 125 days.

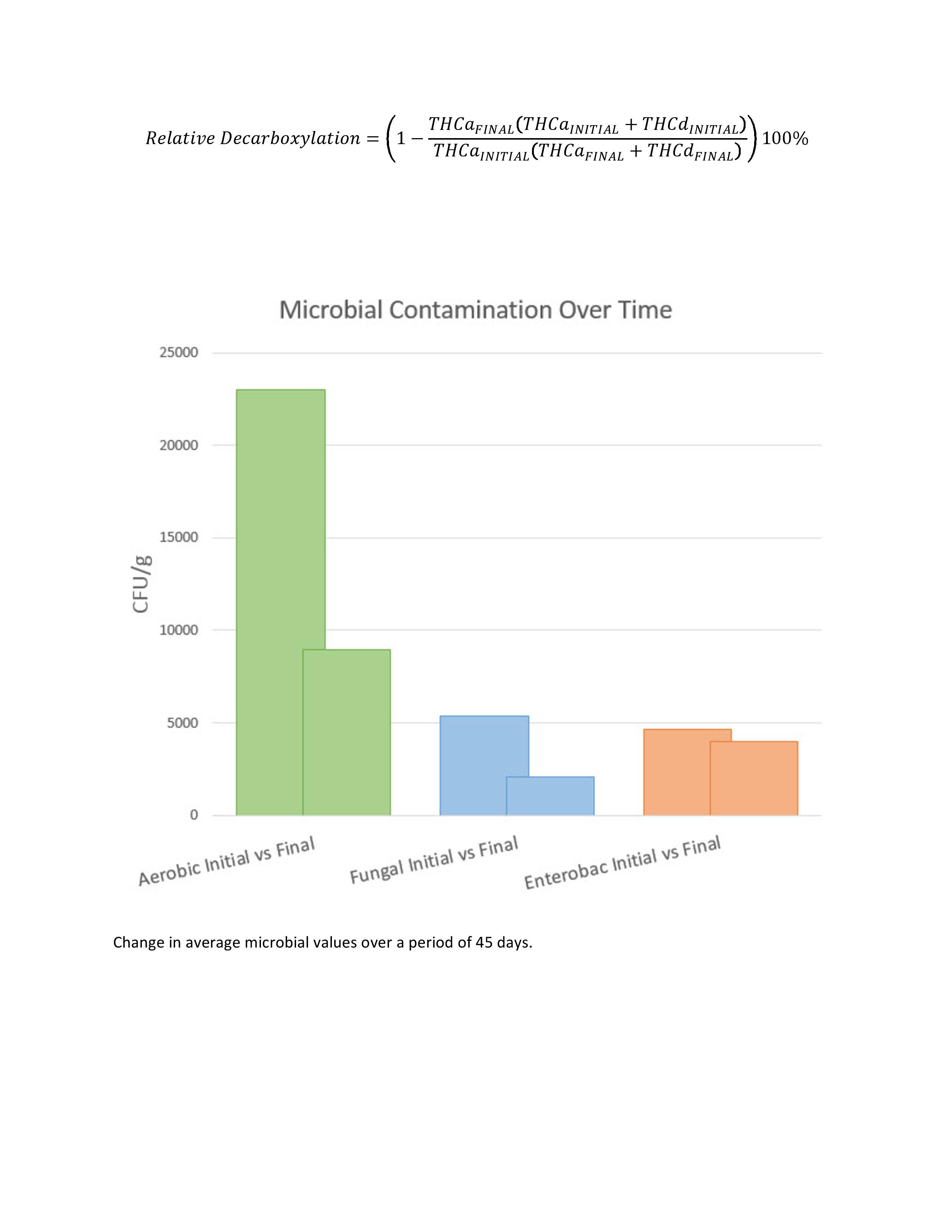

Microbiological analysis was performed using routine methods of microbial enumeration via plate count as described by the Food and Drug Administration’s Bacterial Analytical Manual. Endpoints included colony-forming units per gram (CFU/g) of total aerobic bacterial (or just aerobic), total fungal (or just fungal) and total bile-tolerant gram-negative bacterial (or just enterobac). Three groups of samples representing storage durations of 45 days (sample size=22), 60 days (sample size =21) and 90 days (sample size =11) were each examined to compare initial versus final microbial bioburden using a paired t-test with two tails. Microbiological results were also assessed in comparison to Washington state’s quality assurance failure thresholds for microbial contamination (100,000 CFU/g for aerobic; 10,000 CFU/g for fungal; 1,000 CFU/g for enterobac).

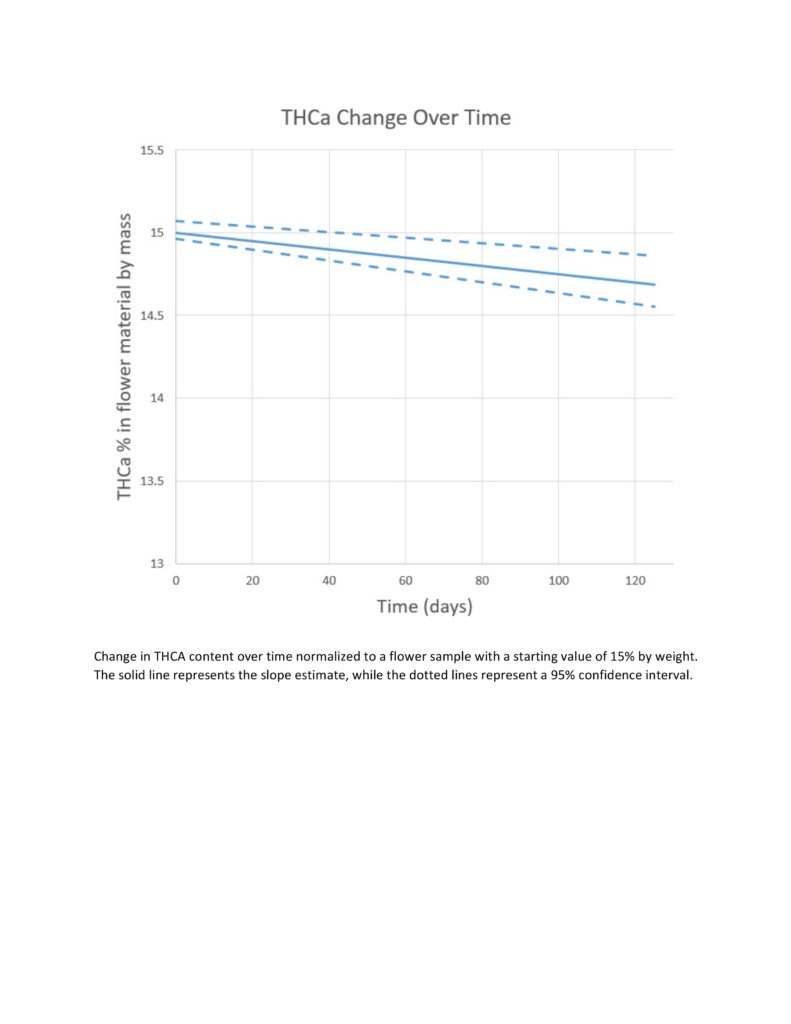

Cannabinoid content analysis (sample size=81) was performed using high-pressure liquid chromatography separation and diode array detection as described by the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia (Cannabis Inflorescence and Leaf), with individual reference standards for each analyte. Endpoints described in this publication include quantifications of both the acidic (THCA) and decarboxylate (THCd) forms of the main psychoactive cannabinoid ∆-9-tetrahydrocannabinol over a continuous date range of one to 125 days from the initial test. Trends in the decarboxylation rate were examined using the equation below, which computes the percentage loss of THCA as it converts to THCd through the process of decarboxylation.

INSERT EQUATION

In all calculations, a conversion factor of 0.877 was used to account for the molecular weight difference between THCA and THCd; the measured value of THCA was multiplied by the conversion factor for all calculations in this publication. Relative decarboxylation was fit to a linear regression for statistical analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant for all statistical tests.

This proposed rule, if put into effect, would have some profound consequences for many stakeholders in the cannabis industry. One potential positive outcome may be that it prompts a discussion about shelf stability, so stakeholders can begin to ask: When should marijuana expire? Should it ever? Does it have a “best by” date? How should it be stored prior to packaging? How do different storage methods affect the rate of change to the marijuana’s quality? What is the best way to package it, and why? How do we know these things? These are complex questions with complex answers, and they warrant our attention.

This article will examine one method of storage and investigate the rate of change in analytical test values over time as the product experiences consistent storage conditions.

The Experiment

Producers and processors of useable marijuana continuously submit samples of flower for quality assurance testing, either as a state-mandated requirement prior to sale, or for their own research and development purposes. Samples of cannabis flower, upon receipt by Confidence Analytics, are completely dried in a desiccator and homogenized into a fine powder before subsamples are drawn for various microbiological and analytical chemistry assays. Most of the homogenized sample remains unused and is stored in an individual plastic bag, sealed with a zip-lock, and kept in a cool, dry, dark environment.

For this experiment, flower samples from 135 lots were selected semi-randomly from the pool of samples tested in the previous 125 days. Samples were intentionally selected to cover a wide range of storage duration and original microbiological contamination values.

These samples had all been initially tested for microbial bioburden and/or cannabinoid content immediately prior to storage.

The initial test values were compared to values obtained after post-storage reexamination, representing a change in value over time.

The Results

Microbiological contamination values for all three contaminants of interest (aerobic, fungal and enterobac) observed under these storage conditions demonstrated a decrease in viable colonies over time. The downward trend was statistically significant at 45 days for aerobic (p-value=0.012) and fungal (p-value=0.035), but not enterobac (p-value=0.444). The decreasing trend was consistent for all three time comparisons. None of the samples in this experiment changed from passing microbial contamination values to failing after storage, and one sample changed from failing to passing.

Decarboxylation of THCA resulted in a statistically significant linear decrease in the concentration of that molecule over time, with the average sample losing 0.0167% of its THCA content per day (95% confidence interval=0.0113-0.0221; p=2.91e-8). This amounts to a loss of 0.5% of THCA in 30 days. If we assume that degradation of THCA through decarboxylation follows this pattern of decay, we’d predict the half-life of THCA under these storage conditions to be somewhere in the range of eight to nine years.

Conclusion

The storage conditions examined in this experiment demonstrate a decrease in both viable microbiological contamination and THCA content over time. While the downward trends for both are statistically significant, only the change in microbial contamination is particularly meaningful at this time scale. With a predicted half-life of nearly a decade, the rate of THCA loss over 125 days is insubstantial, even if it is statistically significant, and an accurate decay curve would be better demonstrated by a study of longer duration. It was observed that microbial contaminants in cannabis flower lose viability over time when stored at desiccated conditions, and the implications of this finding to the marijuana industry could be profound.

A very important point to consider as a caveat to any conclusions drawn from these data is that the trends observed here are true only for the storage conditions described. Certainly, most producers and processors of useable marijuana do not store their flowers completely dried, as was done in this experiment. From anecdotal experience, this author can confirm that even when modest amounts of moisture are present in the container, marijuana flowers can grow mold in the packaging.

A very wide variety of storage methods exist in the cannabis domain, some of which (such as packing with inert gas) might outperform the results of this study in terms of product stability over time. Other forms of storage, particularly when high levels of heat or moisture are present, will certainly perform less well.

Perhaps the most important conclusion to be drawn from these results is the realization that there is much more to learn about the shelf stability of cannabis. Studies such as this can be highly informative to manufacturing processes and legislative decisions, especially in such a young industry. With similar methods to those described here, it should be possible to validate relatively long periods of shelf stability. To that end, we encourage manufacturers of marijuana products to partner with their analytical labs to further the science of this commodity and enhance the professionalism of their craft.

Nick Mosely is the scientific director and part owner of Confidence Analytics, a state-certified cannabis quality assurance laboratory serving producers, processors and collectives throughout Washington state. Confidence Analytics can be reached by email at info@conflabs.com.