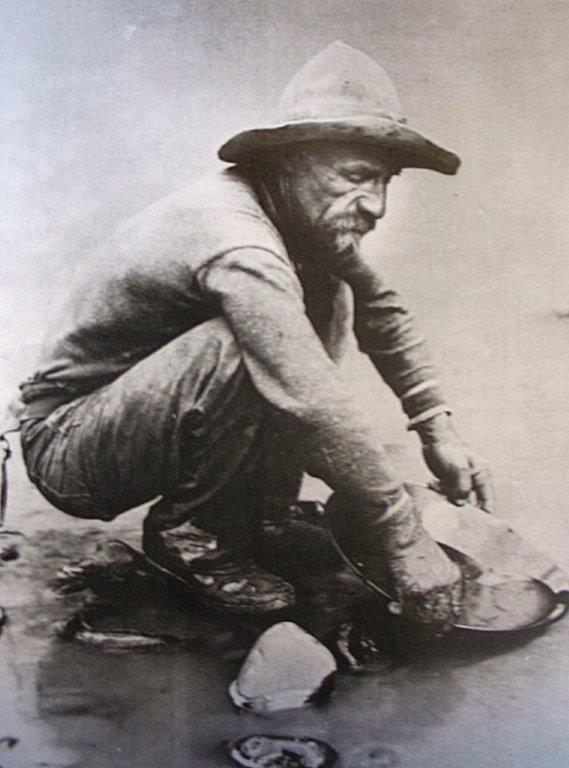

Prospectors once flocked to California with the hopes of striking it rich in gold.

In 1872, two grizzled forty-niners walked into a San Francisco bank with a bag full of diamonds, claiming to have discovered the richest mining field in history at a secret location in the wilderness of Wyoming. Coming, as it did, on the heels of the Gold Rush, the Comstock Silver Lode in Nevada and the more recent discovery of diamond mines in South Africa, their story piqued the interest of some of the richest men in America.

When mining experts confirmed the abundance of gemstones after a blindfolded visit to the site, the interest turned to appetite. The tycoons formed a private investment company that raised (and spent) more than $10 million to exploit the mine, which their experts predicted would yield a million dollars a month in gemstones. The $700,000 they’d paid to buy out the old prospectors seemed like a steal.

Word spread and a “gem rush” to Wyoming began, only to find the whole story had been a hoax perpetrated by the forty-niners. They had fooled the experts by salting the ground with diamond fragments — cheap leftovers from an Amsterdam gem-cutting shop — and made off with their investors’ payout money.

Fears of missing a ground-floor opportunity, combined with greed for quick returns, have driven frauds from ancient Greece to the dot-com bubble. The con artists behind the Great Diamond Hoax of 1872 would surely recognize the hallmarks of their historic fraud in today’s cannabis industry, which is beginning to see its own share of swindles. Indeed, fraudsters often weave a glamorous pitch around the “Next Big Thing” while using secrecy to heighten interest and avoid answering irksome questions.

The Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) recognized this in 2014 when it cautioned about investments in marijuana-related stocks. The hype around the cannabis industry has only increased since. Even legitimate cannabis businesses must resort to less-transparent, less-regulated “over-the-counter” stock markets, private placements or even crowd-funding to raise capital. Federal prohibition effectively bars most cannabis companies from listing on the New York Stock Exchange or Nasdaq, which have stricter registration and disclosure rules.

Irrespective of platform, securities laws require all information disseminated to investors be truthful and complete. Since 2014, a number of cannabis-related frauds have hit the headlines.

In Oregon in 2016, state securities regulators fined a dispensary operator for raising capital by showing investors a forged letter from regulators, ostensibly inviting the company to open dispensaries and promising licenses to do so. The forgery, revealed as such by computer forensics, fooled even the operator’s industry consultants, proving another old adage: “If it sounds too good to be true … it is.”

California’s first major cannabis investor fraud case was brought to court in 2017. MedBox sold cannabis vending machines replete with biometric identification systems and secure cash storage. The company touted itself as a record-breaking growth prospect, led by a man tabbed as the “first cannabis billionaire.” But according to the SEC, the company was nothing more than another round-tripping scheme that sold unregistered stocks through a shell company and reported the proceeds as sales revenue. MedBox and its founder settled the claims for more than $12 million. The case continues against others.

None of these cases involve new or imaginative schemes. Nor are they unique to the cannabis industry. They simply create the illusion of growth to support a deception gilded with stories of new technology and the chance to corner a booming new market.

The antidote is effective due diligence. Investors and their potential business partners must take time and care to independently verify the truth of each material representation they will rely on. Opportunities that come unsolicited or accompanied by high-pressure sales tactics should be rejected outright.

The company’s ownership and capital structure are of particular importance in the cannabis world. Equally important is reviewing financial statements, which should be audited, and must support the valuation of the company. This can be difficult due to the cash nature of many cannabis businesses, but all the more necessary because of it.

Business licenses and permits, along with the applications made in support of them, should also be reviewed. Verification of physical facilities, equipment and inventory is essential. There are, of course, many more steps and the process will vary in every case. Most legitimate companies will not balk at requests for detailed information. If any do, prospective investors can always blame their lawyer — while insisting the details are provided.

Ultimately, the best advice is an adage itself so old it was coined in Latin: caveat emptor.

Anthony Phillips is a founding member of the cannabis law practice group at Archer Norris, which provides transactional and litigation services and legal advice to businesses in California’s legal cannabis industry. Archer Norris has more than 100 attorneys and five offices throughout California.

[contextly_auto_sidebar]