In 2009, Oregon appeared on the verge of becoming a leader in the reemerging hemp industry. The governor had just signed a bill that would allow licensed hemp cultivation in what was already one of the most cannabis-friendly states in the country.

But year after year passed with little to no action from the state Department of Agriculture. The program, fraught with delays and bureaucratic red tape, launched in the spring of 2015 — more than five years after lawmakers approved the measure. Farmers were finally able to start growing crops, but the first year of the program was anything but smooth.

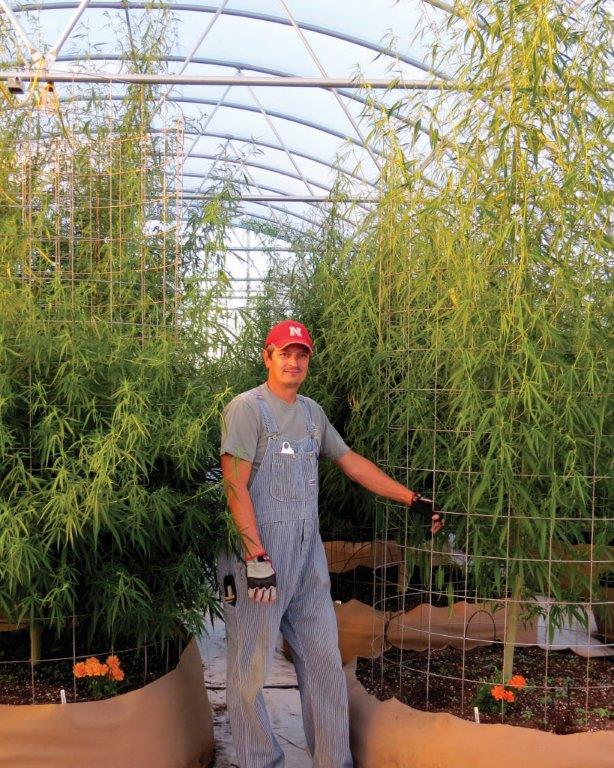

Michael Hughes was one of the dozen or so licensees who were able to plant hemp under the authority of the Department of Agriculture. He found out first-hand the obstacles growers faced and the challenge the state had with understanding and regulating the new market.

Hughes is an attorney by trade, but a farmer at heart. His ancestors cultivated hemp in the Midwest hundreds of years before it was ever viewed as a controlled substance.

The Nebraska native butted heads with the Oregon Department of Agriculture on multiple occasions, but ultimately learned a great deal about the genetics he was working with, the challenges of growing hemp in the high altitude of Bend, and the differences between industrial hemp and psychoactive cannabis. Hughes grew a dual purpose crop for fiber and sensimilla flower in 2015, and discovered the crop required far less water than medical marijuana. He plans to do the same this spring, however, he maintains that until Oregon gets an import permit from the Drug Enforcement Administration to bring in seeds from Europe or Canada, farmers are going to wrestle with genetic drift, unwanted cannabinoid levels and unforeseen problems due to the lack of certified seeds.

Marijuana Venture recently spoke with Michael Hughes as he prepares for his second go-around with state-licensed hemp cultivation in the Pacific Northwest.

Marijuana Venture: What were the biggest lessons learned, both for yourself and the industry in general, from Oregon’s first year of state-regulated hemp?

Some of the bigger plants withstood the frost, so we believe if we have plants out late, they can handle a little bit of cool weather, as long as the temperature rebounds quickly.

We focused on fiber and flower. We did not do any seed production, because we’re mainly trying to stabilize our line of seeds and that’s going to take some time.

I think we’ve got some great potential for really thick fiber, and that requires a production style that’s much different than what’s used in Canada or Europe or any place they’re drilling, and doing close spacing and close rows. We’re going away from that and using bigger spacing so we don’t have the same plant density.

Oregon has so many different micro-climates that each area is going to be a little different. In the valley, they could be putting seeds in the ground in two weeks (mid-April). They don’t deal with extreme cold and frost. Each area is going to be potentially useful for different production. Seed production might be better in some areas, and fiber might be better in others.

MV: What about growing pains from the state’s perspective? What was your takeaway from how the Oregon Department of Agriculture managed the hemp industry?

MH: Ultimately, I think everything we were doing kind of threw the ODA off. They seemed shocked that people were growing for CBD oil and using greenhouses. They were shocked. They tried to get the Department of Justice to rule that the hemp law doesn’t allow for the production of CBD and that we had to have a certain plant density. The Department of Justice said, ‘No, the law doesn’t require that.’ But they did rule that we couldn’t use greenhouses, and based on that we couldn’t start seedlings indoors and transplant them. This would have shut down the industry east of the Cascade Mountains or any high-altitude areas.

Overall, I think there was a big learning curve, and at times it didn’t seem that the Department of Agriculture was fully on board with what was going on.

When I met with the ODA, they said they couldn’t get the DEA permit. That’s when I explained to them that until a producer can get hundreds of pounds of seeds, people aren’t putting them into drills and planting like they do in Canada, France, Spain, Czechoslovakia and China. You need hundreds of pounds of seeds to plant them that close.

MV: Now that you’ve gone through one season, how will you adjust the growing methodology going forward?

We’re probably going to be doing a little greater plant density, but we’re not going to be using a drill. We’ll work primarily with cuttings and we’ll use our two best cultivars from last year. Basically, we’re going to plant them in the ground when they’re two to three feet tall. Nice straight rows, where we can examine the individual plants, keep the two cultivars separated, and see how fast we can get it to grow outdoors. The flower and CBD are important, but this year we’re really going to be focusing on how many big, thick, fibrous plants we can get and what kind of growth we can get in our three-month growing period.

MV: What do you see as the ultimate end use for the fiber you’re able to harvest?

MH: You’ve got the two fibers from the stalk — the bast fiber and the hurd fiber — and we’d hopefully like to see them used for building materials.

I’d like nothing more than to load up a semi-truck with giant, 15-foot-long hemp stalks. With the thickness of the stalks, you’ll still be able to get that long bast fiber. We believe the two cultivars we’re going to be growing this year will average 12 to 15 feet in height. True American hemp. Canadian and European hemp are not going to have that height. We believe with those long outside fibers, and a tremendous amount of hurd fiber, that there’s going to be uses for it somewhere.

If we grew them over in Douglas County or Jackson County, I suspect some of these cultivars would grow into 20-foot plants.

We had some that were between 15 and 17 feet that blew people’s minds. Even experienced Oregon pot growers have never seen anything like that.

We believe we can grow fields of trees that don’t use a whole lot of water, and if we do it right with other nitrogen-fixing crops — like alfalfa, which is grown commonly in this area — that it can be a good, sustainable rotation crop. Hopefully the fiber can be used to revitalize some of these lumber mills that have been shut down, because the timber industry has been hurt.

MV: When do you anticipate putting plants in the ground outside?

MH: I think at this point, we’re looking at the long-term forecast, but mid-May would probably be the earliest we’d start. Mainly we want to get past the last day of frost. We hope to get in excess of 2,000 plants in the ground, so it’s going to be quite the project.

We anticipate planting in the last couple weeks of May and the first week of June. We’re not as worried about an early frost in the fall as we are of a late frost in the spring, when they haven’t been out there long enough to develop their roots.

We’re a little more sheltered this year, but we still anticipate some winds. Last year, we were right out in the open. There were times when the wind was blowing those hemp plants almost straight down to the ground.

I believe the hemp plants actually like the wind; people couldn’t believe how those plants would be bent to the ground, and the next day they’d pop straight back up. It’s a pretty durable plant.

MV: The Bend Bulletin published a story about some of your hemp plants testing above the 0.3% THC threshold. Although the THC levels were still miniscule, they caused a lot of hassle for you and the state. Tell us a little more about that.

MH: The funny part of that story is that I think we had 18 plants of the two cultivars that tested high out of the thousands we planted. I had to inquire how the state would like us to destroy them. I don’t know if there was even five pounds.

I said there’s not enough to merit starting up my tractor and running over it with my brush hog, but I’ll start my push mower and mulch it.

Because we were able to show that the other four cultivars had no THC in them, we were able to segregate the plants. They put an embargo on our crop in November, and we finally got the embargo lifted in February, so we’re in the process of determining the best way to extract the cannabinoids. There are the traditional methods people use to extract psychoactive cannabis, CO2 or BHO. We’re looking at some other methods that might be safer.

During the embargo process, I was on the phone with the Oregon Department of Agriculture and the Oregon Department of Justice. They told me that my case had been referred for criminal prosecution. The district attorney in my county said he hadn’t heard anything about that, so I think they were just threatening me. I tried to explain to them that this cannabis with 1% and 2% THC doesn’t have any value. As hemp it doesn’t have any value to me. As a medical cannabis grower, it doesn’t have any value. The attorney for the Department of Justice blew up at me and starting giving me a lecture about how this is a controlled substance.

I told them, ‘You guys realize this is not marketable. I can’t divert this to the black market unless I want to get killed.’

I kept trying to joke with them: ‘If I gave this to a medical patient, I’m pretty sure they’d beat me up.’

For hemp, I want stuff that’s 0.3% THC or lower. I tried to explain genetic drift; I tried to explain phenotype drift; I tried to explain breeding dioecious plants. They didn’t understand it. The ODA is still refusing to get a DEA permit, even though I anticipate we’re going to have more than 14 applicants like we did last year. I wouldn’t be shocked if 100 people apply for licenses this year.

People are now going to Colorado to get seeds, and Colorado has had its own problems with seeds. It took European countries about a decade to get to 0.3% THC. That’s why now when you order certified seeds, they’re from a certified seed producer. When you open-pollinate dioecious plants, you have a tremendous amount of genetic drift. And when you’re talking about a micro-amount of cannabinoids, the potential is even crazier.

It took us about four months to go through this embargo and consent order. That’s for one person and 18 plants. And I’m an experienced cannabis breeder. I’ve been breeding cannabis for 20 years.

If a hundred people get licenses and they get their seeds from wherever, then the state is going to have a problem on its hands.

The craziest thing is that hemp is the most regulated form of cannabis production in Oregon right now. Recreational may change that with seed-to-sale tracking, but we haven’t even entered that yet.

I’m not sure how many medical grows have been inspected by the Oregon Health Authority, but I’m pretty sure my hemp farm had more inspections last summer than most medical grows that have been growing under the OHA for the last 10 years.

MH: We’re looking forward to get going again. The Legislature recently passed a bill allowing us to use greenhouses — kind of a novel idea that we would be the only crop in the state that couldn’t use greenhouses. My ultimate plan is to have greenhouse seed production here, where I can do large-scale breeding and stabilize our genetics.

I’ve got some really good American genetics. I’ve got the height; I want to amplify the CBD levels and keep the THC levels down. There’s definitely some breeding I want to do, but as any dioecious plant breeder, I want to control it. I don’t want to just stick it out in a field. Eventually it will be able to go out into a field, but right now I want to get the line stable.

This year, we’ll do another fiber and flower crop, and hopefully much bigger amounts of fiber. Then in the next year and a half, we’re looking at doing some full-scale breeding.

MV: Where do you stand regarding the subject of cross-pollination between the industrial hemp and medical marijuana industries?

MH: I feel somewhat responsible for starting the cross-pollination controversy back in 2014, down in Southern Oregon. In front of a bunch of medical growers, I asked Edgar Winters (the first person in Oregon to receive a hemp cultivation license) if he thought cross-pollination would be an issue, and at the time, he didn’t.

Right now, with the production acres we have, I don’t necessarily see it being an issue. But I do know that cross-pollination can and will become an issue if hemp production for seed increases.

If you have an 80-acre field of hemp, there will be a limited radius where hemp pollen could cross-pollinate hops or other cannabis plants.

That could definitely cause problems. But on an 80-acre plot, if that’s the only one in the county, the potential for cross-pollination is pretty minimal. If there’s a medical crop right on the other side of the fence line, yeah, that’s probably going to get pollinated.

The real issue with cross-pollination will be if, for example, Lane County has 300,000 to 500,000 acres of hemp. Now you’re going to have millions of hemp plants pollinating at the same time and the pollen count in that area will become concentrated. If there are a few weeks of hot, dry weather, that high pollen count will remain in the air and there will be issues when it gets to that scale.

The real issue with cross-pollination will be if, for example, Lane County has 300,000 to 500,000 acres of hemp. Now you’re going to have millions of hemp plants pollinating at the same time. That will create what I call a pollen flume.

If there are a few weeks of hot, dry weather, that pollen flume just kind of sticks there. There will be issues when it gets to that scale.

It’s the Corn Belt where you’re going to see the large-scale hemp seed production, and Oregon and the Pacific Northwest will have more niche crops, where they’re growing it for CBD or they’re growing it sensimilla or growing it for big fiber. The Corn Belt — places like Indiana, Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Ohio, Illinois — is where you’ll see the large-scale production. And it will be almost impossible to grow outdoor cannabis in those places.

There’s going to be a lot more hemp farmers in Kansas than cannabis farmers, just by the politics and the nature. There’s nothing wrong with that. I don’t think Washingtonians, Oregonians and Californians will mind selling weed to Kansans, if it’s legal. Hell, they don’t mind doing it illegally, but when it’s legal, they’ll really like it.

It’s like with everything: Certain regions of the country grow certain crops, usually because the climate allows it to grow there. Hemp for seed will grow great in that Midwestern climate.